“Whoever is defeated, naturally, pulls out of the arena; whoever is exhausted takes a seat. But that changes nothing. New fighters replace those who pull out; others rise to take the place of those who sit down. And if today we all pull out of the arena, tomorrow members of the new generation will rise, holding the old flag up high in their hands because they too want to live their national life.”

Levon Shant’s words crystalize the great Armenian’s deeply held belief in the new generation. A generation that he created, that passed on to the one that followed its passion for soaring ever higher; a generation that today continues its committed steps, “holding the old flag up high.” On March 1, 2020, Toronto Armenians have the opportunity to experience a singular day, a celebration, by the Hamazkayin Kladzor Chapter, of Levon Shant—playwright, pedagogue, a president of the National Assembly of the first Republic of Armenia, a founder of Hamazkayin and of the Djemaran in Beirut.

At the entrance of the Hamazkayin Theatre at the Toronto Armenian Youth Centre, guests look at an object covered in a veil. The covering is white, with birds embroidered in blue thread. Inside, from the stage, Shant’s profile greets the guests. Under it is his signature and the dates 1869–1951.

The lights dim and the emcee, chapter secretary Shogher Jelladian, reads a brief biography. Shant was born in Istanbul. His birth name was Levon Nahashbedian (Seghposian). He attended the local school in Üsküdar (Scutari). He lost his parents as a child and was sent to Ejmiadzin alongside other young men, including Gomidas, to attend the Gevorgian Seminary.

After his studies, he returned to Istanbul and started writing under the name of Shant. The Hairenik published his satiric novella, “Mnak Parovi Irigune” (The evening of goodnight), as well as his first poems. He moved to Germany, where he studied for seven years. He took courses in pedagogy, psychology, and natural sciences and continued to write.

In 1899, Levon Shant moved to the Caucasus and worked as a teacher while also part of Hovhannes Tumanian’s Vernatun literary circle in Tiflis.

Shant returned to Istanbul but moved, in 1913, to Europe and thus was spared death in the Catastrophe.

In 1919, he was elected to the National Assembly of the Republic of Armenia and became a president of the parliament. After Armenia became a Soviet republic, Shant moved first to Persia, then to France; he taught and wrote for four years in Marseille. He was then invited to Alexandria to teach at the Boghosian national school; the principal was Nigol Aghpalian, the literary critic. In Cairo, in 1928, alongside a group of intellectuals, he established the Hamazkayin publishing and cultural association. A year later Shant and Aghpalian moved to Beirut, where, in 1930, Shant founded the Armenian Djemaran. He served as principal until his death at the age of 82.

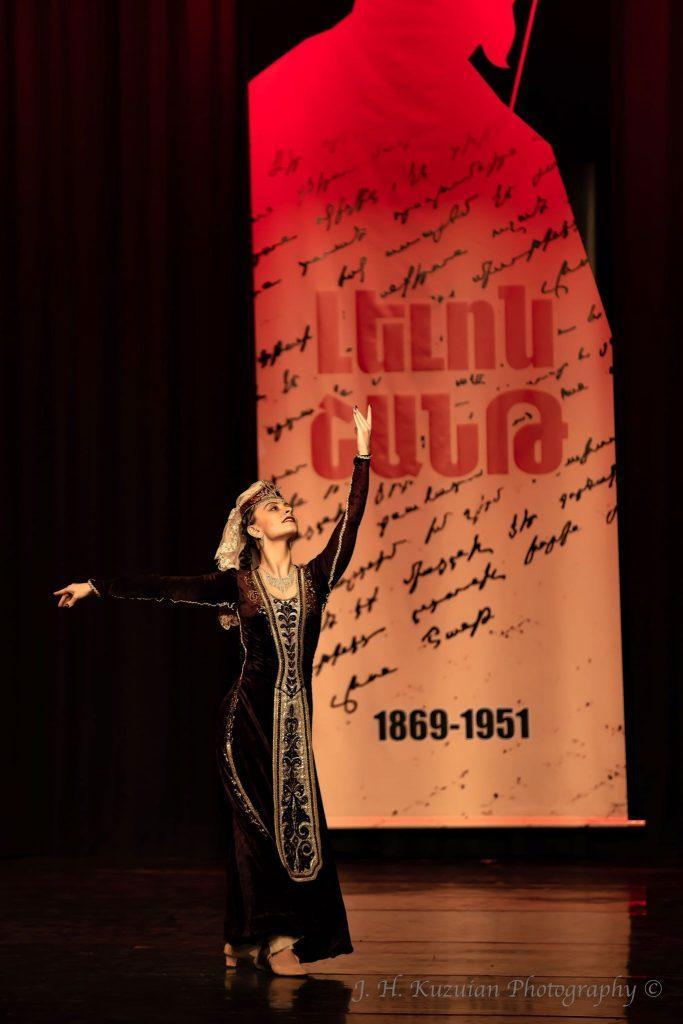

Edgar Baghdasarian’s “Prelude” begins the artistic program for the day. The pianist is Antoinette Manoogian, the talented granddaughter of the musician Hagop Manoogian. In a glorious velvet dress and with proud steps, Maria Manoogian, well known for dancing with the Hamazkayin Erepuni Ensemble, takes the stage. Azat Gharibian directs a performance of the pleasant “Akhaltsikhe” to extended applause.

The musician Vanig Hovhannesian has transformed Shant’s poem “Anush Hovig” into a song. Sarine Sarkisian of the Hamazkayin Kousan Choir gives a delicate interpretation of the song, accompanied by Mr. Hovhannesian on piano. The applause is enthusiastic. A video, “Kaghdni Tghtabanag” (Secret file) is shown.

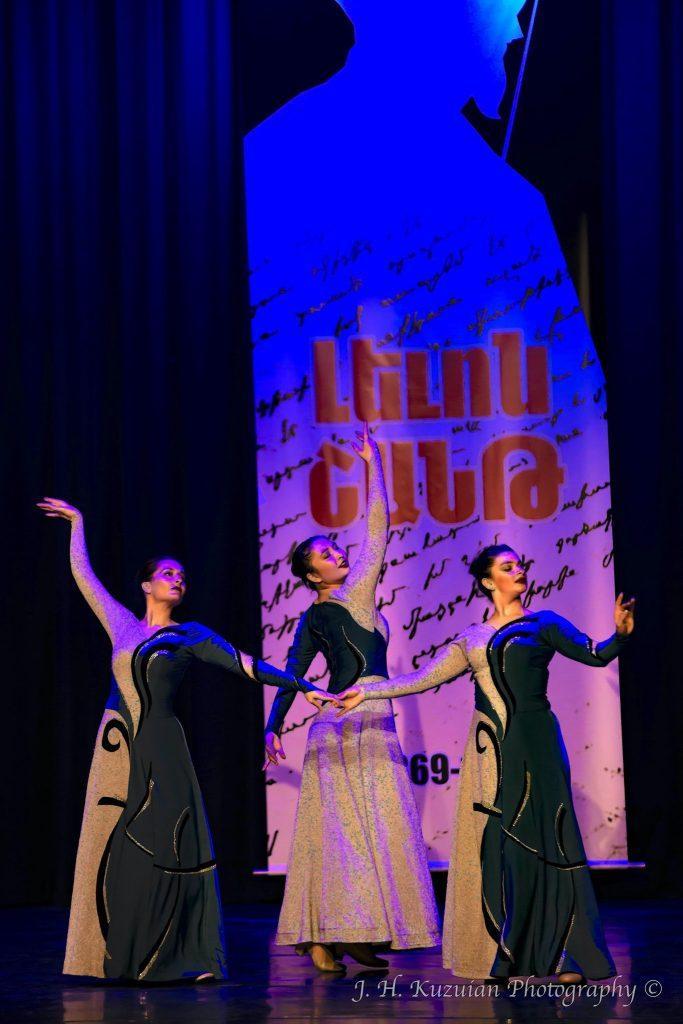

Now Central Executive Board member Dr. Viken Tufenkjian, invited especially from Montreal, delivers a keynote.

Dr. Tufenkjian has served in various capacities in the Armenian Revolutionary Federation and Hamazkayin. Director of the Hamazkayin Bedros Atamian Theatrical Group is one of those capacities. His Holiness Aram I, catholicos of the Great House of Cilicia, has awarded Dr. Tufenkjian with the Mesrob Mashtots Medal for his dedicated educational, social, and cultural activity. He holds a Ph.D. in English from the Université de Montréal, where he also studied education.

“It is beyond doubt,” Dr. Tufenkjian says, “that Shant, who opened new paths in the fields of literature, pedagogy, philosophy, and national life, is one of the shining intellectual stars in the Armenian firmament. We must, therefore, pay our debt of respect to Levon Shant and accord him his place in Armenian literature.” In Beirut, Dr. Tufenkjian says, more than ten thousand mourners attended his funeral, but in Armenia he was sadly labeled “an anti-Armenian zealot.” The reason, he says, was the literary atmosphere of the time, forced by the ideologues of the Communist Party of the Armenian SSR.

What is sadder, he adds, is that thirty years after Armenia regained its independence, when Tumanian and Gomidas are remembered with numerous public celebrations, there is hardly a mention of the great satirist Yervant Odian and a mere two conferences about Shant, with scant attendance. “Shant has always been variously labeled an inaccessible, Western Armenian, godless, or philosophical writer,” he added.

The chairperson of the Hamazkayin Central Executive Board, Dr. Megerdich Megerdichian, has called Shant “the consummate Armenian,” Dr. Tufenkjian recalls. Shant brought together in his person the Western Armenian of his birth, the Eastern Armenian of his life in the Caucasus, along with his European higher education, to create a unique, unifying figure in the Armenian world.

Turning to Shant’s plays, it’s easy to see his idealism and aspirations for all humanity. Tufenkjian mentions a few of Shant’s works to point out that Shant’s heroes never lose hope, don’t get emotional, and always aspire upward. “Shant brought an entirely novel mentality to modern Armenian literature; understanding it required intellectual capacity and unambiguous dedication,” Dr. Tufenkjian says. “This is probably one of Shant’s alleged crimes. Say we were not ready for his novel worldview a hundred years ago; but not even today?”

The literary critic Hagop Oshagan didn’t have much praise for Levon Seghposian’s work or heroes back then. “What story do they tell? What people do they belong to?” Oshagan wrote, excluding Shant’s heroes from the Armenian people. The speaker adds interesting details about Shant’s beliefs about the Armenian language and tells stories about Shant’s personal discipline and industry. He confesses, however, that what interests him the most is the attention Shant lavishes on self-knowledge. He wraps up by saying that Shant is a one-off; seventy years after his death he continues to draw us to his thoughts through the symbolism of his works and the currency of his thoughts.

The keynote allows guests to open new windows into their knowledge of Levon Shant the man and the writer. The emcee gives Dr. Tufenkjian a copy of Matthew Karanian’s most recent book as a gift.

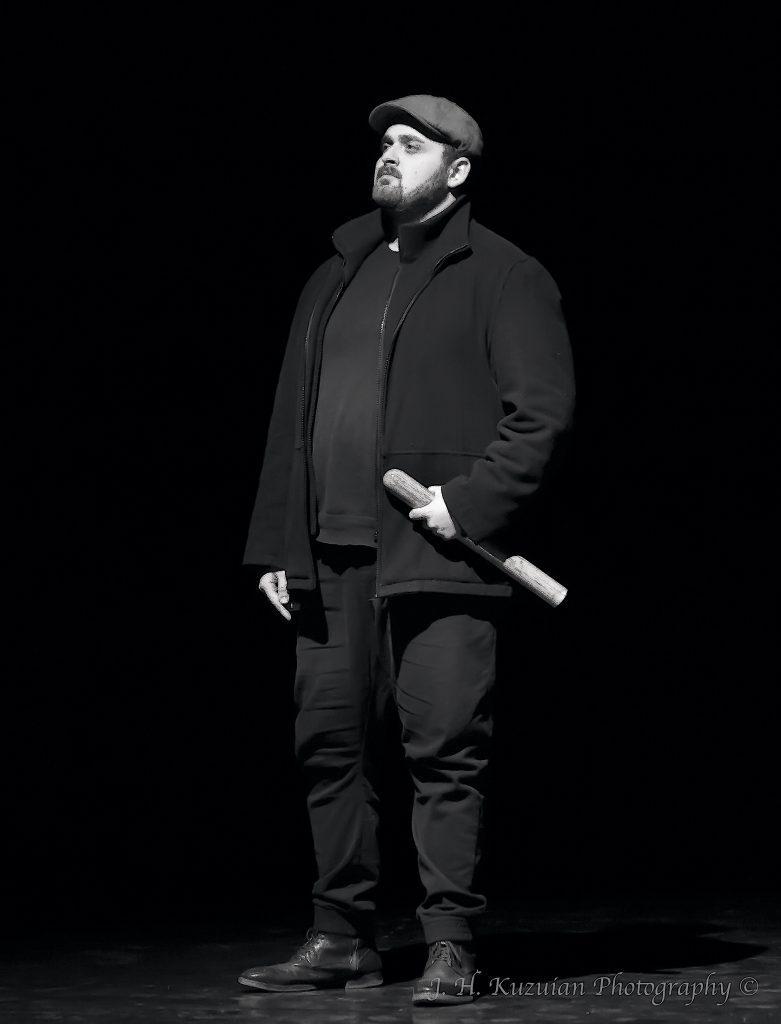

The stage is dark. In utter silence, we hear Moushegh Karakashian’s deep voice. Aren Mnatsakanian, the “Night Watchman,” walks across the stage, his footsteps sounding like a ticking grandfather clock. He remembers his childhood. In the spotlight we can see children sitting cross-legged and a grandmother is telling them about the legendary Mher. The actors started at the Hamazkayin M. and H. Arslanian Djemaran and are now students at the ARS Day School here: Lori Berberian, Varak Mesrobian, and Narod Kelebozian. There is moving recorded music and the movements of the actors and their facial expressions capture the imagination of the guests. “Kisherabahe” (Night watchman) is among Shant’s more penetrating stories. It demonstrates his unwavering will to soar above the painful circumstances of everyday life.

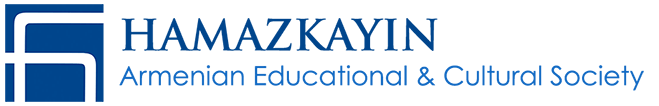

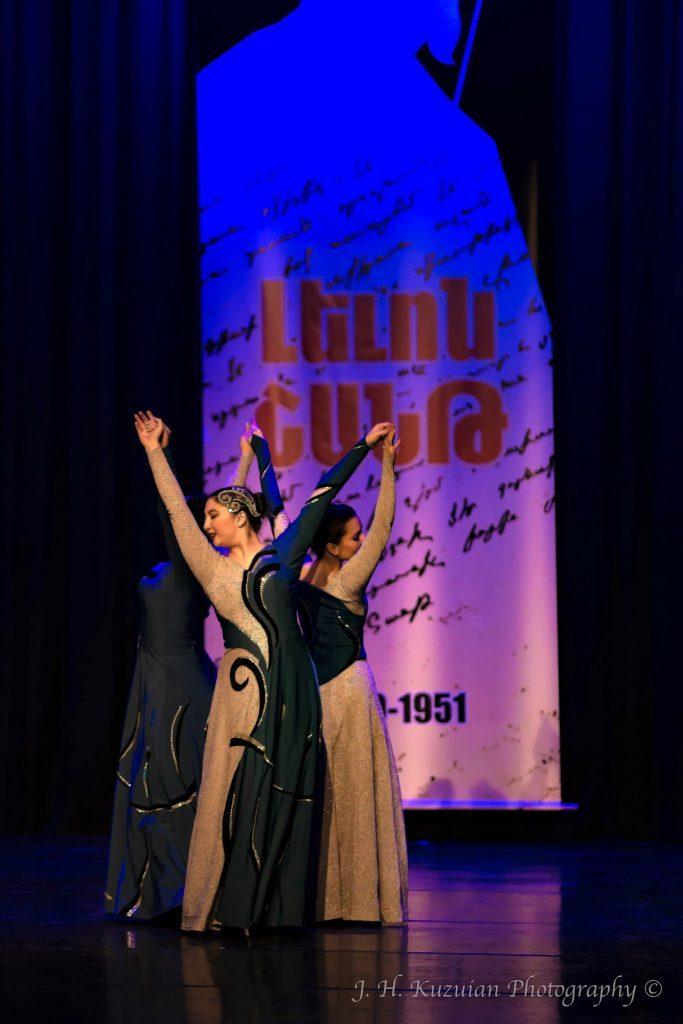

We turn the page. This time it is the harp that grabs our hearts. Vani Yacoubian, Lana Der Bedrossian and Dzila Kouyoumdjian Kourjakian of the Hamazkayin Erepuni Dance Ensemble are wearing flowing costumes and their coordinated movements create harmony in the eyes of the guests. The dance teacher and artistic director Nelly Karapetyan is to be congratulated.

Levon Shant’s character of “praising the life of the ideal” is once again demonstrated in the story, “Yes Badranke Siretsi” (I loved the deceit). Lori Berberian recites the piece with clear diction and understanding.

At the conclusion of the artistic program, the emcee invites the chairperson of the chapter executive board, and of the literary committee, Tamar Donabedian Kuzuian, the sculptor Hagop Janbazian, and his wife Juliette Janbazian to the stage. Mr. Janbazian created the bust of Shant and is one of the donors to the project. His works are on display in Armenia and in Canada, the United States, Lebanon, and Israel. Ms. Donabedian Kuzuian presents the couple with a painting by Samuel Tavadyan, a young artist from Artsakh, as a token of the community’s appreciation. She also expresses words of deep gratitude to donors Dr. Ani Hasserjian and Levon Hasserjian, who aren’t present.

The time has come. At the entrance to the theatre, Dr. Tufenkian, Ms. Donabedian Kuzuian, and ARF Toronto Gomideh chairperson Sevag Kupelian unveil Levon Shant’s bust to enthusiastic applause. Levon Shant has found his worthy place in the Toronto Armenian Youth Centre, across from the Armenian school, at the entrance to the Hamazkayin Theatre. How very fitting. Even the date is fitting, as the Djemaran Shant established in Beirut turns 90 this month. Mr. Janbazian delivers an emotional address. Coffee and kata are served.

It is an emotional moment. Shant’s face smiles at all of us. Let Shant serve as a source of inspiration to each of us to aspire to the best, never losing hope, living a virtuous life as an Armenian, laying claim to Armenian culture, Armenian schools, and the Armenian language.

--T.D.